Dozens of people gathered in McKeldin Square on December 18 to honor more than 80 unhoused Baltimoreans who have died this year ahead of a brutally cold winter that’s expected to worsen the death toll.

The city’s unhoused residents are facing a lack of shelter beds and freezing temperatures, a potentially lethal combination for a vulnerable population that often opts for the streets because of safety concerns at the facilities. Winter shelters have already been open for most of the last month under the Mayor's Office of Homeless Services “Code Purple” directive, but, despite the risks of hypothermia, frostbite, and death, the city has yet to finalize shelter plans to bolster its winter bed capacity.

Those who advocate for their unhoused neighbors have sounded the alarm about both the quality of shelters and the city’s apparent failure to prepare for the winter.

“They are behind, and they are waiting until winter comes to do something about it,” said Mark Council, lead organizer for Housing Our Neighbors, a nonprofit advocating for the rights of unsheltered Baltimoreans.

“At this time, it’s too late for them to do anything about it. They should have had something already; winter is going to come regardless. What’s sad about it is that people are going to refuse to come into a shelter or hotel because they feel as though it’s safer outside in these cold elements. We know that them being out here with the cold will kill them.”

With homelessness on the rise, there are just 562 shelter beds in the city. Rather than expanding permanent shelter spaces in response, the city is mulling a 90-day shelter stay policy to restrict the amount of time someone can be in a shelter — a proposal that has been met with fierce backlash among activists.

When temperatures drop, there are 300 additional winter shelter beds, though advocates have argued they should always remain open. Regardless, the agency’s data shows that the demand vastly outnumbers the supply. Last year, for example, 20,000 people called the shelter hotline for help, and city officials have confirmed that people had to be turned away.

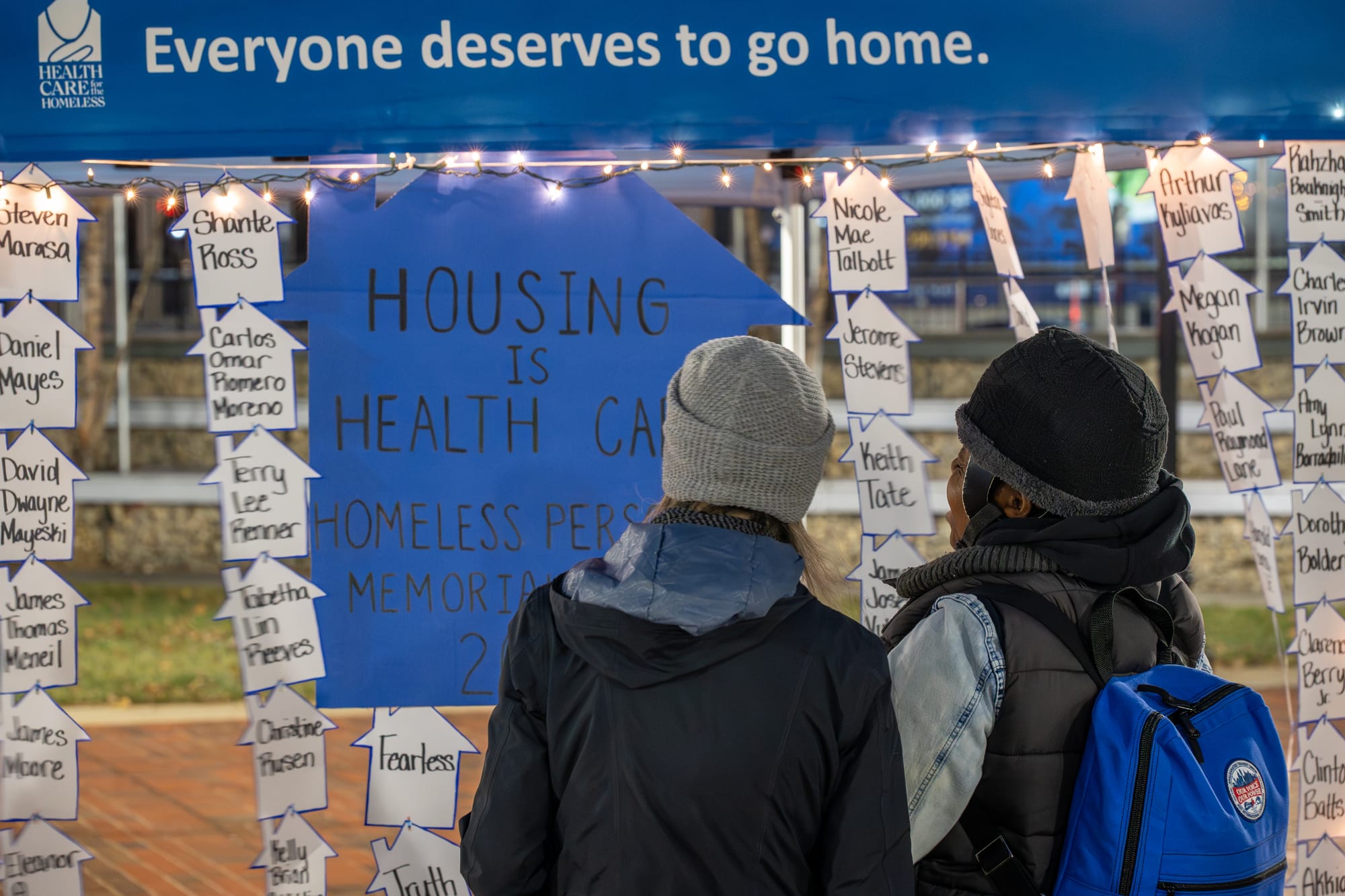

The inaccessibility of quality care during times of need has been a resounding theme among those who have had to live on the streets or in shelters. At the Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day on December 18, advocates read the names of people confirmed to have died in Baltimore this year by Health Care for the Homeless, one by one. Each name was an individual who died a preventable death, and although there was a sense of hope that the system could change, the stories of loss woven into attendees’ remarks painted a grim picture of the state of homelessness in Baltimore.

Although the dangers of extreme temperatures for the unsheltered residents are well-documented, it’s unclear just how many have died due to the cold in recent years. Like the city's attempts to gauge the total number of unhoused individuals in Baltimore, the death toll cited by advocates at the memorial service is likely an undercount.

City and state agencies would not provide more granular data about deaths among the unhoused population. Baltimore Beat is awaiting a response to a public records request.

Standing in front of cutouts of homes bearing the names of those who died, Deirdre Hoey, a behavioral health therapist at Health Care for the Homeless, emphasized the need for them to be honored.

“There are names of people on this list that are truly loved, and sometimes we’re the only ones who get to know them,” Hoey said. “A lot of people on this list were denied memorials, funerals, and other ways to remember them.”

Even without exact numbers, the impact of policy failures and extreme temperatures on the unhoused population is clear — and that comes amid an assault on housing and homelessness policies at both the federal and local levels.

A federal judge on December 19 issued a preliminary injunction blocking the federal government’s plan to drastically limit the amount of grant funds that can be spent on permanent housing, which officials have said will decimate affordable housing programs in their communities.

The federal government planned to cap the amount of funding that jurisdictions can use for permanent housing at 30% of total funding, which would kick at least 700 Baltimoreans out of subsidized housing. President Donald Trump had already signed an executive order in July to criminalize homelessness, ramp up forced institutionalization of those with mental illnesses and substance use disorders, and defund life-saving harm reduction programs.

The judge’s decision was in response to a lawsuit from 20 states, including Maryland, and numerous nonprofits. They sued the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, alleging it was illegally stripping away aid from tens of thousands of unhoused Americans.

“We know that permanent housing, and only permanent housing, is the solution to homelessness,” said Antonia Fasanelli, executive director of the National Homelessness Law Center, who spoke at the vigil and serves as co-counsel in the case against the Trump administration. “It’s not forced drug treatment, not involuntary mental health commitment, and defunding affordable housing is certainly a step in the wrong direction.”

The parties who sued the federal government over the anticipated homeless policy changes scored a temporary victory. However, even without federal interference, Baltimore officials have sparred over what must be done to protect the city’s unhoused population.

That came to a head at a Baltimore City Council Housing and Economic Development Committee hearing in November, when Councilman James Torrence grilled the city’s homeless services office for more than two hours over their handling of shelters ahead of the winter.

“I care about the people who have to sleep on the streets,” Torrence said. “I don’t want them to freeze and die.”

Torrence repeatedly cited a survey of 74 current and former shelter residents conducted by Housing Our Neighbors during the hearing. It showed that residents at the city’s homeless shelters are often unaware of the process to file grievances about safety, cleanliness, and other matters.

Residents rate the conditions of shelters as 5.1 out of 10 on average. Shelter residents faced insect infestations; brown-colored water coming from showers, toilets and faucets; expired or moldy food; and a lack of wheelchair accessibility, the survey found.

The councilman also claimed he’d been told that the city didn’t begin looking for additional winter overflow shelters until September, which Ernestina Simmons, director of the homeless services office, denied.

“Our goal is to ensure that no Baltimore City resident in need, including people experiencing homelessness, is left without a warm place to sleep on Baltimore’s coldest nights. We are currently working with other city agencies to identify a permanent winter shelter overflow location to our portfolio,” agency spokesperson Jessica Dortch said on November 26.

As the city looks to expand access to winter shelters, it’s operating with just eight outreach workers as more than 2,000 people in Baltimore are experiencing homelessness on any given night, 70% of whom are Black, according to the city’s 2025 Point-in-Time Count.

That marks a 26.5% increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness over the year prior.

“We have recorded 26 deaths last winter, and that terrifies me,” said Christina Flowers, founder of Belvedere Real Care Providers and a local advocate for people experiencing homelessness.

“It’s like we’re sitting back and waiting for premeditated deaths. We have to be focusing and making sure we are securing the type of triaging and assessment that these individuals need, so that they’re not only coming into the shelter but also getting their trauma and mental health needs met.”

Those needs are also under threat.

The prevalence of substance use disorder among unhoused individuals has skyrocketed in the last few years, according to the city’s Point-in-Time Count.

Compared to 23% of people reporting having substance use disorder two years ago, a whopping 77% reported being addicted to a substance this year. Moreover, 67% of unsheltered residents also reported having a “serious” mental illness.

City officials have said that, in response to the rise in substance use issues and recommendations from an independent consultant, the agency is now working to implement on-site behavioral health and substance use services. But not only are they struggling with a lack of capacity, but the city as a whole is losing some critical programs that benefit the population.

On November 14, the Historic East Baltimore Community Action Coalition announced it would be shuttering due to funding issues. As a result, coalition programs like The NEST, a 10-bed shelter for unhoused youth, and Dee’s Place, an addiction recovery center, will also cease operations.

Dee’s Place closed on December 12, and The NEST will close on January 30, though the organization is looking for other entities to “continue the mission,” Board Chair Brandon Lockett said.

Shortly after the organization announced its closure, Mayor Brandon Scott unveiled a plan on December 4 for the Baltimore City Department of Social Services to help relocate youth and young families at risk of homelessness.

Under the plan, the agency will identify older youth in foster care and other out-of-home care programs to live at the 44-unit Restoration Gardens 1, a housing complex for previously homeless teenagers and at-risk youth in Park Circle. The agency will also identify young families at risk of homelessness to live in the YMCA of Central Maryland’s Geraldine Young Family Life Center in Upton, which has 12 units.

Health Care for the Homeless has also unveiled plans for a 42-unit affordable housing development in downtown Baltimore, with most units reserved for people earning at or below 30% of the city’s median income. The complex, called Sojourner Place at Park, is slated to open to residents in early 2027.

The complex is the third project between the nonprofit and Episcopal Housing Corporation, with Sojourner Place locations also in Argyle and Oliver. Those three projects alone provide permanent housing for hundreds of low-income residents, including those who were formerly unhoused.

“The opposite of homelessness, as we know, is home,” said Kevin Lindamood, executive director of Health Care for the Homeless, at the December 18 vigil. “We commit to a future where there will be no need for memorial services like this one because we’ve brought everyone in and left nobody out.”

Comments