Harm reductionists from Baltimore and beyond are backing a new iteration of a bill in this year's General Assembly session that has paraphernalia criminalization in its crosshairs — part of a renewed effort to combat the racist War on Drugs in Maryland.

Dozens of people, ranging from harm reduction organizers to abstinence-based recovery advocates, gathered in Annapolis last week for Overdose Prevention Advocacy Day. After rallying at the Lawyers Mall on a frigid Tuesday morning, they lobbied lawmakers to support or oppose a slate of bills being considered in this year's session. For those fighting for the rights of drug users, it was paraphernalia legislation cross-filed in both chambers that took priority, with the day culminating in a hearing before the House Judiciary Committee.

"Legally obtained items should stay legal. Point blank, period," said Candy Kerr, communications manager of the Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition. "It's the association with drugs that makes it illegal, allowing police officers to stop and harass people who have paraphernalia on them."

Unlike previous versions of the legislation, it would not decriminalize paraphernalia. Advocates are instead pushing for a streamlined bill this year that would repeal laws criminalizing paraphernalia entirely, bypassing the inevitable – and likely lengthy – debates over what items fall under that umbrella.

Even though syringe service programs have existed in Maryland for more than three decades, the laws on the books allow police to arrest drug users if they cannot prove that items like syringes and stems came from the programs. Even if they can prove it, the simple possession of those items allows cops to initiate contact with individuals without any indication that they're illegal.

Law enforcement data has made it clear who they are targeting.

A Baltimore Beat investigation last year found that nearly all of those who are arrested and charged with drug-related crimes, including paraphernalia, are Black.

That number peaked at 96% in 2021, the same year that the city recorded its most fatal overdoses on record. A little over 1,000 deaths that year were attributed to overdoses, more than two-thirds of whom were Black, according to data from the Maryland Department of Health.

In 2024, 92.5% of those arrested for drug charges were Black.

"Our current laws do not keep us safer," said Del. Karen Simpson, a Frederick County Democrat sponsoring the House bill. "They're not stopping the production, distribution or usage of drugs. Our current laws have been a distraction from serious crimes, and they have been used as a weapon against our struggling communities and the people who are trying to serve them."

The legislation would make it easier to access sterile supplies, which prevent the spread of HIV and other diseases, without fear of being arrested. And while it may not seem like an overdose prevention measure at face value, dismantling a key component of the War on Drugs would undoubtedly save lives.

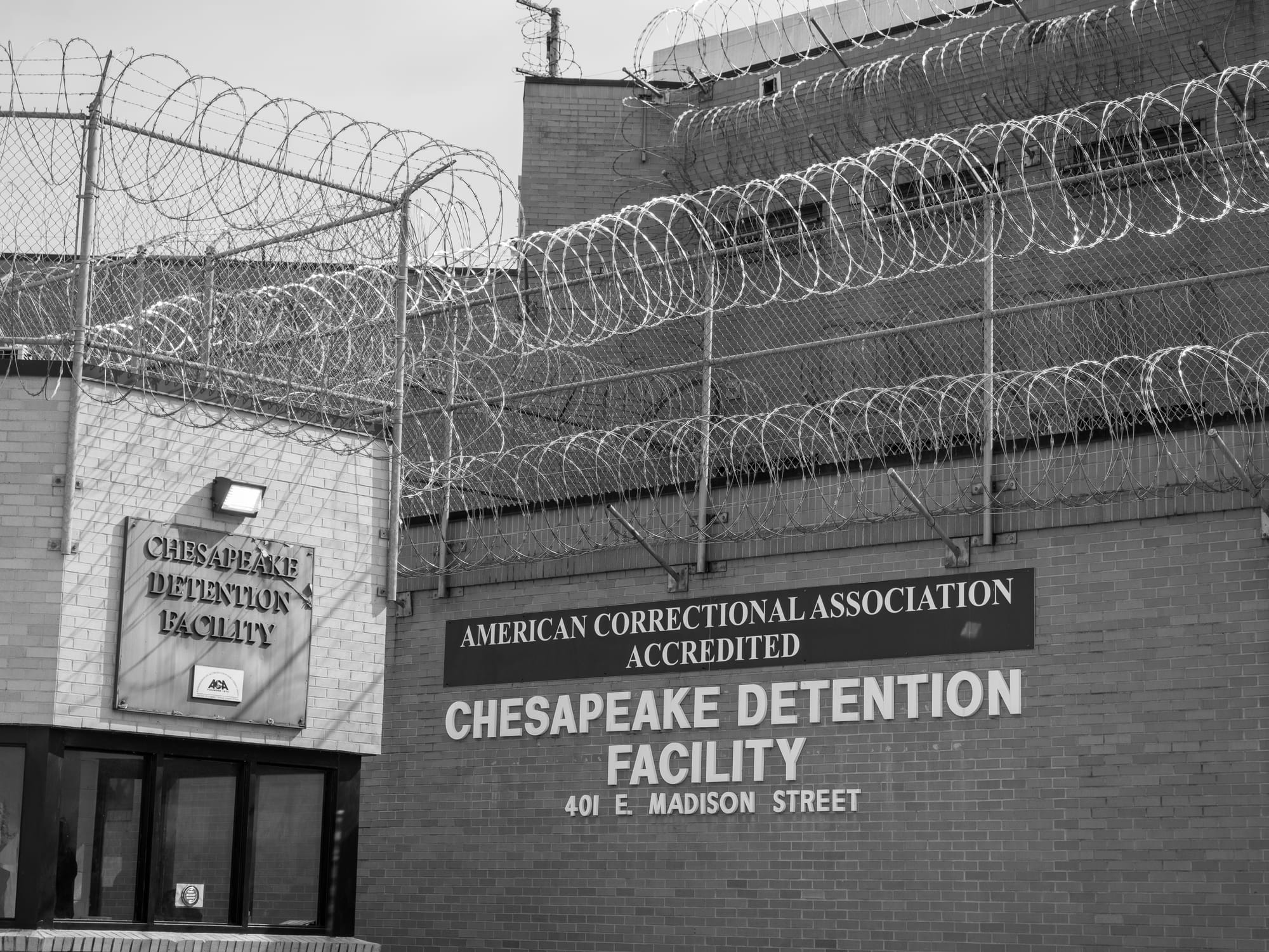

Paraphernalia laws are often used to initiate drug users into the criminal justice system or weaponized as tack-on offenses to bolster cops' cases against vulnerable individuals. As studies have shown, the result is that the destabilizing nature of incarceration, along with drug-war policing, dramatically increases fatal overdose rates.

Efforts to tackle paraphernalia criminalization have had mixed results. Back when it was a decriminalization bill, it passed both chambers in the General Assembly but was vetoed by former Gov. Larry Hogan in 2021.

While the upper chamber had the votes to override the veto, Senate President Bill Ferguson — who has also played a role in the deaths of other proposed drug policy reforms over the years — never pursued it.

Last year, the bills died in committee.

Ferguson's apathy toward life-saving reforms has also held up legislation to legalize overdose prevention centers, which allow people to use drugs in facilities under medical supervision. Legislation to permit the facilities to open in Maryland also languished in committee last session.

Those facilities are considered the gold standard of harm reduction, although bills to legalize them were not introduced this year. Advocates say that lawmakers are too distracted with other matters to give OPC legislation a fair shot this session, and the fact that it's an election year means those in power are less likely to take up reforms deemed too controversial.

Despite studies repeatedly demonstrating the efficacy of OPCs, there has been little appetite among lawmakers to legalize and ultimately save countless lives.

"It's disappointing they have decided not to bring that forward this year," Kerr said. "Our gameplan is to come back next year better and stronger and try to get it passed. And we're always working on OPCs on the city level."

City-sanctioned OPCs appear to be an uphill battle. Mayor Brandon Scott has refused to commit to using his power to unilaterally permit sites to open, and Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Taylor has indicated that the city won't pursue OPCs to avoid risking federal funding under President Donald Trump.

Meanwhile, as drug users continue to die at unprecedented rates — although annual death tolls have dropped substantially in the past two years — there's a bipartisan effort to fill jails and prisons with those who sell them drugs.

As they look to pass the paraphernalia bills, harm reductionists are trying to kill a pair of bills that were introduced at the eleventh hour that would significantly ramp up penalties for drug distribution, potentially providing more ammunition for police and prosecutors carrying out the drug war.

Those bills would create a 20-year maximum sentence for those who distribute fentanyl or heroin that leads to death, also known as "drug-induced homicide." On top of a law passed in 2017 that increased the maximum sentence for opioid dealers to 30 years, those who sell drugs could see as many as 50 years behind bars.

Like the paraphernalia legislation, those bills died in committee last year.

"The penalties are insane, and it will discourage people from reporting overdoses," said Dan Rabbitt, policy director at Behavioral Health System Baltimore, who added that he anticipates those bills facing the same fate this year.

Harm reductionists argue that repealing paraphernalia laws would allow drug users to utilize syringe programs without fear that they could be arrested for having their supplies. They oppose the drug-induced homicide legislation because it ramps up a criminalized approach to drug policy and would likely cause even more preventable deaths.

Caught in the middle of the policy debates, however, are drug users themselves.

The focus on the 90-day legislative session in Annapolis should not distract from what is happening back home in Baltimore, nor should it lift any burden off the shoulders of local officials who have the power to implement change at the city level.

Baltimore, for instance, already had de facto decriminalization of not just paraphernalia but all low-level drug crimes under former State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby. It was Ivan Bates, her successor, who recriminalized the simple possession of a syringe or stem and undo years of progress in combating the drug war.

The Redux Newsletter is co-published by Scalawag Magazinee, an abolitionist publication covering oppressed communities in the South. Support them today.

Local officials seem incapable of fully comprehending the harm done during Bates' tenure. At the same time, however, they insist that relying on state-level reforms is the best way to effect meaningful, progressive drug policy in Charm City.

The mayor has backed efforts to decriminalize paraphernalia and legalize OPCs in the General Assembly, joining other officials in a performative effort to appear as though they care about the well-being of drug users.

But he, like many members of the Baltimore City Council, has only sparingly used his power to enact drug policy reform. The inaction has been most evident in Scott's refusal to fight for city-sanctioned OPCs, despite researchers suggesting that Baltimore could establish sites by issuing an emergency declaration. New York City also demonstrated in 2021 that coordinated efforts among city agencies can make it possible.

With those in power balking at opportunities to liberate drug users from the confines of the carceral system and inevitable death, the people must demand more.

Legislative pushes at the state level are imperative. Yet boots-on-the-ground organizing pressuring local officials — the ones who claim to represent and fight for everyday Baltimoreans — is equally important in the movement to end a lethal, racist drug war that has festered in the city for decades.

What too many fail to realize is that drug users are the same "everyday Baltimoreans" they purport to defend. And if they truly care about their constituents, they'd afford them the right to autonomy and life itself.

Read the last Redux Newsletter: "Baltimore's flawed mass OD protocol is a consequence of its failure to end the drug war"

Baltimore's new mass overdose protocol begins with a promise: The War on Drugs is over in Baltimore, and the racist beast of punitive drug policy is no longer running the show.

Mayor Brandon Scott made the case before the Maryland Senate Finance Committee last week. With city health officials by his side, he emphasized the need for compassion and prompt action as he reflected on a string of three mass overdose events in Baltimore's Penn North neighborhood last year. Though none of the dozens of people who overdosed died because of prompt action from harm reductionists, the incidents rocked the low-income Black community and prompted a flurry of racist propaganda that harkened back to the New York Times’ infamous 1914 article, “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends’ Are a Southern Menace,” which ultimately led to one of the first racist drug laws in the US.

Things have changed since then, officials argue. And care, not handcuffs, is at the center of the city's overdose prevention plan, officials say.

Read the full newsletter here.

Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data has been updated with the latest local, state and national data

There were 568 overdose deaths in Baltimore in 2025, marking a historic 27% decrease from the year prior, according to preliminary data from the Maryland Department of Health.

That death toll will likely change as causes of death are finalized, but the decline mirrors the downward trend seen nationally. This was the second consecutive year that Baltimore saw a notable decrease in deaths; there were 777 deaths — a 25.5% decrease from the year prior — in 2024.

The numbers indicate that the city's fatal overdose rate continues to trend downward after years of climbing, with the death toll twice surpassing 1,000 people.

However, the preliminary data also shows that low-income Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore continue to see the highest death rates. Those same neighborhoods are also the most heavily policed, with residents significantly more likely to be arrested on drug charges,

Check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard here.

Click here to learn more about harm reduction resources in the Baltimore area.

Matter News: "Ohio’s Recovery: The past, present, and future of the overdose crisis"

Ohio’s relationship with and response to substance use has always obscured fundamental human rights problems.

Alcohol prohibitionists were fueled as much by racism and xenophobia as they were by religious zeal. The effects of the drug war have impacted Black and Brown people and poor people more than anyone else. Methamphetamine use is a way to stay awake while working multiple shifts or when rough sleeping. And voters approve access to cannabis and then legislators try to limit it.

The surge in opioids that began in the late-1990’s was as much about lack of adequate health care as it was about shady “pill-mills.” When access to pills slowed, there was greater access to heroin and then fentanyl, and then a rise in blood borne diseases. The subsequent sluggish rollout of syringe service programs in Ohio – and an outright ban in Licking County – was rooted in stigma and not science.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments