Flanked by a cadre of cops and city officials, Mayor Brandon Scott on Wednesday announced the takedown of a drug trafficking organization in Curtis Bay — yet the aftermath of these coveted busts can be deadly for drug users.

The joint operation, conducted by law enforcement agencies at every level of government, yielded 11 arrests and was touted as a valiant effort under the city's Group Violence Reduction Strategy during a press conference at the Curtis Bay Recreation Center. Officials made it clear that drug dealing and the violence it's associated with have no place in Baltimore, issuing a stern warning to those who continue despite offers to divert them from the lifestyle.

"In order for the strategy to work, we have to hold those who choose to engage in behaviors associated with violence consistently, time and time again, even after being given the chance to change their life, accountable," Scott said. "We will not tolerate groups like this one that ignore the strategy's mandate to put down the guns, contribute to the proliferation of illegal narcotics on our streets and continue to do harm in our community."

As officials stood in front of television cameras on a sunny afternoon in South Baltimore, they exuded the bravado often associated with drug busts.

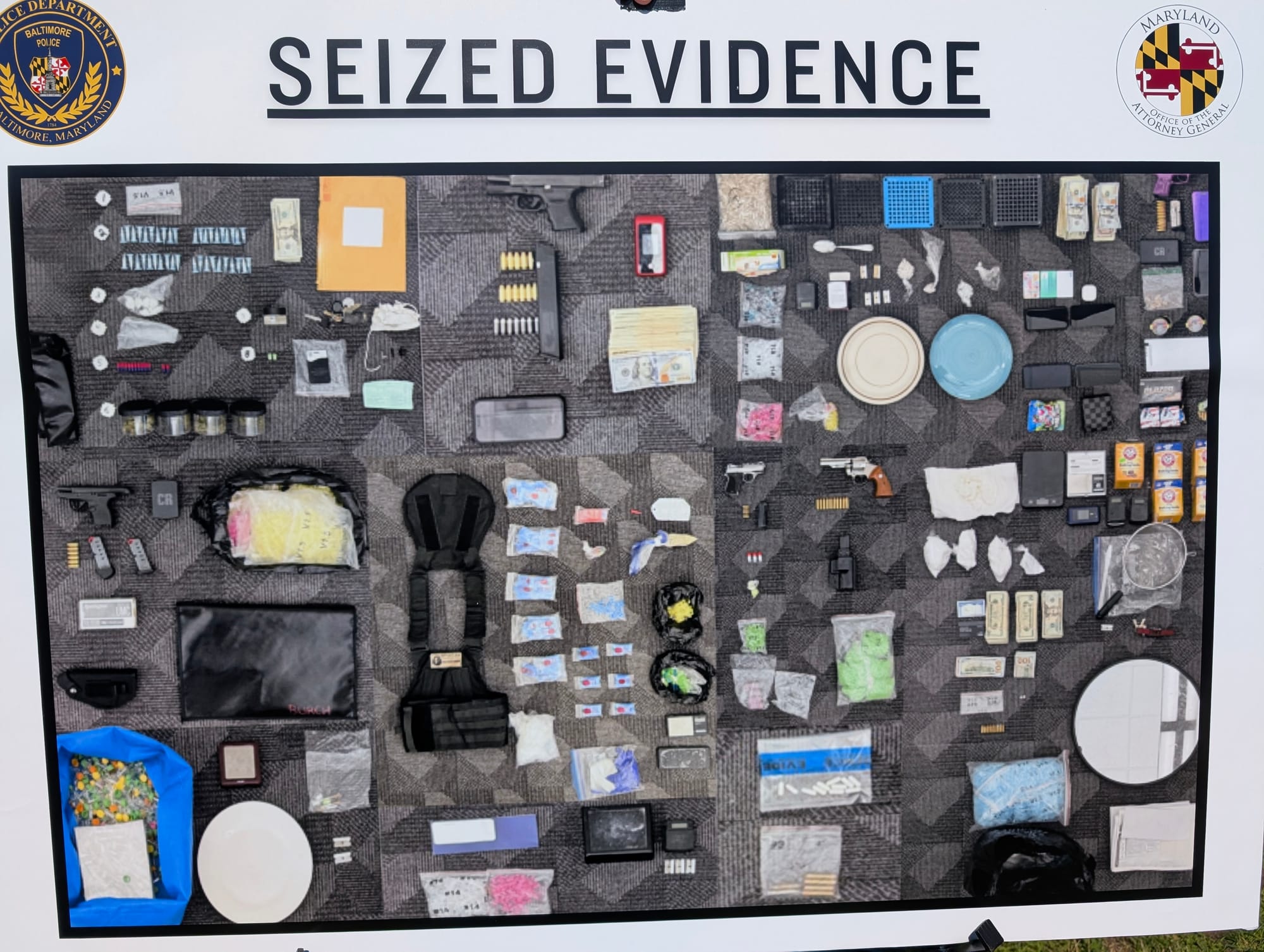

One placard to Scott's right showed the locations where the group operated and sold drugs. Another placard displayed the drugs, weapons and "paraphernalia" seized by law enforcement — the hallmarks of a classic drug war press conference.

However, contrary to the celebratory nature of such announcements in Baltimore and elsewhere in the nation, the repercussions of police operations targeting those who sell drugs can be a death sentence for those who use them.

The cops may remove the drugs from the streets, but they're replaced as quickly as they were seized. After busts, drug users respond to the disruption in the drug supply by taking their business elsewhere. Studies have shown they're often met with deadlier dope.

Fatal overdose rates can increase dramatically as a result, researchers from Harvard University found in 2023. They laid out their case in an article titled "Here's why police drug busts don't work," which cited research conducted in Indianapolis.

"We found compelling evidence that fatal and nonfatal overdose rates doubled following police raids to seize opioids and other drugs. In the week following a drug bust, fatal overdoses doubled within 500 meters of the event, and within two weeks of police action, first responders were called to administer naloxone to reverse drug overdoses at twice the rate, suggesting an increase in non-fatal overdoses," the article states.

The research was predicated on two decades' worth of literature showing the disruption of drug markets is "consistently associated with excess overdose deaths." The premise is simple: In place of the drugs taken off the streets, drug users turn to riskier suppliers.

And that risk is seemingly growing in severity by the minute. Fentanyl has become the norm, though more potent synthetic opioids such as nitazenes have begun to emerge in the market. Moreover, adulterants such as xylazene and medetomidine have caused a wave of concern among public health experts, notably for their resistance to naloxone.

Local and state officials have instead asserted that drug users aren't the victims of law enforcement actions. Instead, it's those who sell them who are to blame.

"We know that drug trafficking not only drives violence in Baltimore but also further victimizes those vulnerable individuals struggling with substance abuse, many of whom are losing their lives to overdose at an alarming rate," said Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown.

Drug enforcement is considered a key tenet of violence prevention efforts in Baltimore, including through the GVRS program.

The initiative launched in January of 2022 as a partnership among the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, the State's Attorney's Office and the Baltimore Police Department. Since the program's inception, the city has connected 218 individuals to "life-changing" services, officials said. There have also been 407 arrests.

At its heart, the program aims to prevent violence by offering social services to those who are at the highest risk of becoming involved in violent crime. While it attempts to connect those individuals to resources, the police will crack down with the full force of the law if their warnings aren't heeded.

Officials on Wednesday asserted they are not only reducing violent crime — homicides and nonfatal shootings are down 22.9% and 32.1% this year, respectively — but also battling the overdose crisis by arresting those who sell drugs and seizing their supply.

"As we've been doing GVRS throughout the city and as we've seen these takedowns of drug organizations, it also coincides with overdose deaths going down in Baltimore," Scott said. "We're going to continue to expand harm reduction, and MONSE is leading on that effort here."

When asked for specific data to support the claim, the mayor said there has been a correlation between the launch of GVRS and the period in which overdose deaths began to decline in Baltimore "writ large."

Available data does not paint a definitive picture. The program is relatively new; it launched in the Western District in 2022, expanded into the Southwestern District in 2023 and then stretched into the Central and Eastern districts last year, according to the mayor's office.

Scott's office did not provide data showing a link between a decrease in overdose deaths in areas covered by GVRS and those dates when asked follow-up questions.

Some areas in the Western District — such as those in the 21217 ZIP code, which includes Penn North and Sandtown-Winchester — have seen a steady decrease in overdose deaths since 2022, according to data from the Maryland Department of Health.

Other areas have experienced fluctuations in their death toll, which is also true for total overdose deaths in the city.

The city's overall death toll dropped 8% in 2022, the year GVRS launched, according to state data. Yet they increased by 5% in 2023, which preceded a historic 31% drop in overdose deaths last year.

The fluctuating data neither supports nor refutes the mayor's assertion, though overdose deaths have been decreasing nationwide since 2023, when the U.S. saw the first decline in overdose deaths in five years. Questions arise, therefore, as to whether the decrease can be at all attributed to GVRS or simply to a national phenomenon.

The city has claimed that the organization's drugs were linked to an increase in fatal overdoses in the area. Specific data was not provided, and available data does not indicate there is an abnormally high number of overdoses in Curtis Bay.

In fact, the ZIP code in which the organization was busted has one of the lowest annual overdose death tolls in the city. The 21226 ZIP code, in which Curtis Bay is located, saw 12 overdose deaths in the year-long period ending in February. Annual data shows it's had some of the fewest deaths of any ZIP codes for which data is available.

Still, city agencies have worked to help those who use drugs as police action forces changes upon the supply, said MONSE Director Stefanie Mavronis.

"Our team at MONSE has mobilized city services in partnership with BPD and a host of other agencies in the Curtis Bay community to prevent other groups from capitalizing on the power vacuum left in the wake of this takedown," Mavronis said. "This includes substance abuse and harm reduction services through the city's health department, the Mayor's Office of Homeless Services and other wraparound supports tailored to the community's needs."

The importance of harm reduction does not seem to be lost on city officials as they attempt to crack down on drug suppliers.

Baltimore's harm reduction infrastructure is fairly robust despite the mayor conceding there is room for improvement, and those resources should be leveraged to ensure the safety of drug users as the supply changes.

Councilwoman Phylician Porter, whose district includes the area, noted after the press conference that the harm reduction resources that were mentioned are offered regularly rather than ramped up in response to police action.

Mentions of harm reduction aside, however, it was abundantly clear that cops and city officials were more concerned with cracking down on drug suppliers in the name of violence and overdose prevention.

With that in mind, the underlying issue is that the assertion that drug enforcement helps curb overdose deaths is an argument without data to support it. The same is true for the argument that drug policing has a causal relationship with a decrease in violent crimes, which officials claimed to be the case during a hearing on "open-air drug markets" last month.

The drug trade is indeed linked to violence, but the reason for the correlation has been debated. Ramping up enforcement measures, though, may not have the intended effect, as evidenced by a 2011 study in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

"The existing scientific evidence suggests drug law enforcement contributes to gun violence and high homicide rates and that increasingly sophisticated methods of disrupting organizations involved in drug distribution could paradoxically increase violence. In this context, and since drug prohibition has not achieved its stated goals of reducing drug supply, alternative regulatory models for drug control will be required if drug market violence is to be substantially reduced," the study states.

Similar results have been found elsewhere in the world. A recent study out of the U.K., conducted by RAND Europe, found that drug-related law enforcement is more likely to increase violence than reduce it, Filter reported on Wednesday.

“The available evidence suggests that drug-related law enforcement activities are of limited effectiveness in reducing violence. Indeed, more studies demonstrated an association between drug-related law enforcement activities and increased violence than decreased violence," according to the report.

In a nation where drug policy remains significantly influenced by the decades-old War on Drugs, it's inconceivable that cities such as Baltimore would stop or even reconsider busting drug trafficking organizations.

None of this is to say that violence prevention efforts are an inherently negative thing. Though the number of overdose deaths last year tripled that of homicides, violent crime remains a significant problem in Baltimore.

However, if cops are going to enforce drug laws derived from racist and destructive illusions about those who use them, the city must at least look beyond actions that churn out fodder for the prison-industrial complex and photo ops.

Officials must consider the public health consequences of these actions, which include potentially severe disruptions to an already deadly drug supply. It also must be acknowledged that busts such as what were advertised do not get drugs out of the hands of those who use them.

The reality is clear as day: These busts push those who use drugs toward more contaminated sources, which has been proven to increase fatal overdose rates. And that's something that Baltimore cannot afford.

After a decade of surging death rates, it wasn't until last year that the city saw its first notable drop in deaths. That's not enough to warrant confidence amid a devastating overdose crisis.

Complacency would be a disservice to drug users. The same is true for police actions predicated on a strenuous connection between drug enforcement and decreases in crime.

Miss last week's newsletter? You'll want to check it out:

Buttressed by a windfall of opioid restitution dollars, Mayor Brandon Scott's $4.7 billion budget proposal is nonetheless shrouded in uncertainty as to whether harm reduction initiatives will be funded to their full potential.

Scott unveiled his proposed budget for the upcoming fiscal year on Wednesday, coming on the heels of a barrage of austerity measures from the White House. As those who use drugs in Baltimore continue to die preventable deaths at astronomical rates, the fate of billions of dollars meant for public health initiatives, including money for services related to mental health and substance use, is essentially up in the air.

“The reality is you can’t really have a contingency plan because no one knows — I don’t think they even know — what they’re doing to do from one second to the next,” Scott said. “We might have to come back and make adjustments to this budget based on what happens in D.C., and we have a great team that’s prepared to do that.”

Click here to read the full newsletter.

Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard is frequently updated with the latest local, state and national data:

Preliminary data recently released by the Maryland Department of Health covers total overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending in February. Overall, deaths have continued to trend downward.

There were 633 overdose deaths reported in Baltimore, a death rate of 108.1 per 100,000 people. The highest concentration of deaths remains in the Black Butterfly, specifically in West Baltimore.

Statewide, there were 1,463 deaths. Besides the city, the counties with the most deaths were Baltimore County, Prince George's County and Anne Arundel County, which saw 166, 148 and 109 deaths, respectively.

Check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard here.

Click here to learn more about harm reduction resources in the Baltimore area.

"Amid DOGE Cuts Elsewhere, the DEA Is Actively Recruiting," Filter reports:

At a time when agencies across the federal government are seeing massive spending and workforce cuts under the Trump administration, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is actively ramping up recruitment—urging people to join the agency on the frontlines of the “war on drugs,” even if they currently work as a “coffee barista” or otherwise have a non-law enforcement background.

DEA hasn’t just been largely exempt from the slash-and-burn approach to federal spending, which has been orchestrated by Elon Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) he’s running. The agency is apparently positioned to expand.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments