There's been a growing consensus in Baltimore about the importance of harm reduction as the city's unprecedented overdose crisis rages on — but that support has continuously come with caveats.

As the harm reduction movement grows, city leaders still refuse to abandon punitive drug policies born out of the War on Drugs. And as a string of public hearings held by committees of the Baltimore City Council closed out this week, some officials indicated that the commonsense, life-saving approach to drug use is simply a means to an end. It's important, they said, but the true enemy lies in the brains of those who use substances despite negative consequences.

To put a spin on a quote from former President Richard Nixon, an architect of the drug war: Addiction is public enemy No. 1.

"I think the immediate goal for us is to reduce overdose deaths, but after we've done that, the goal is then to break down the addiction across our city," said Councilman Mark Conway, chair of the Public Safety Committee, during a hearing on Tuesday.

"So while naloxone is a really important tool for reducing deaths, I think the next step is to address the addiction."

Conway's comments seem to reflect the feelings of many public officials, all of whom appear to support harm reduction but to different degrees. Take, for example, the fact that Councilman Ryan Dorsey is the only official who has vocally supported city-sanctioned overdose prevention centers.

Despite a baseline support for care for active drug users, however, the assertion that it's simply a mechanism by which sobriety is achieved is exceptionally problematic.

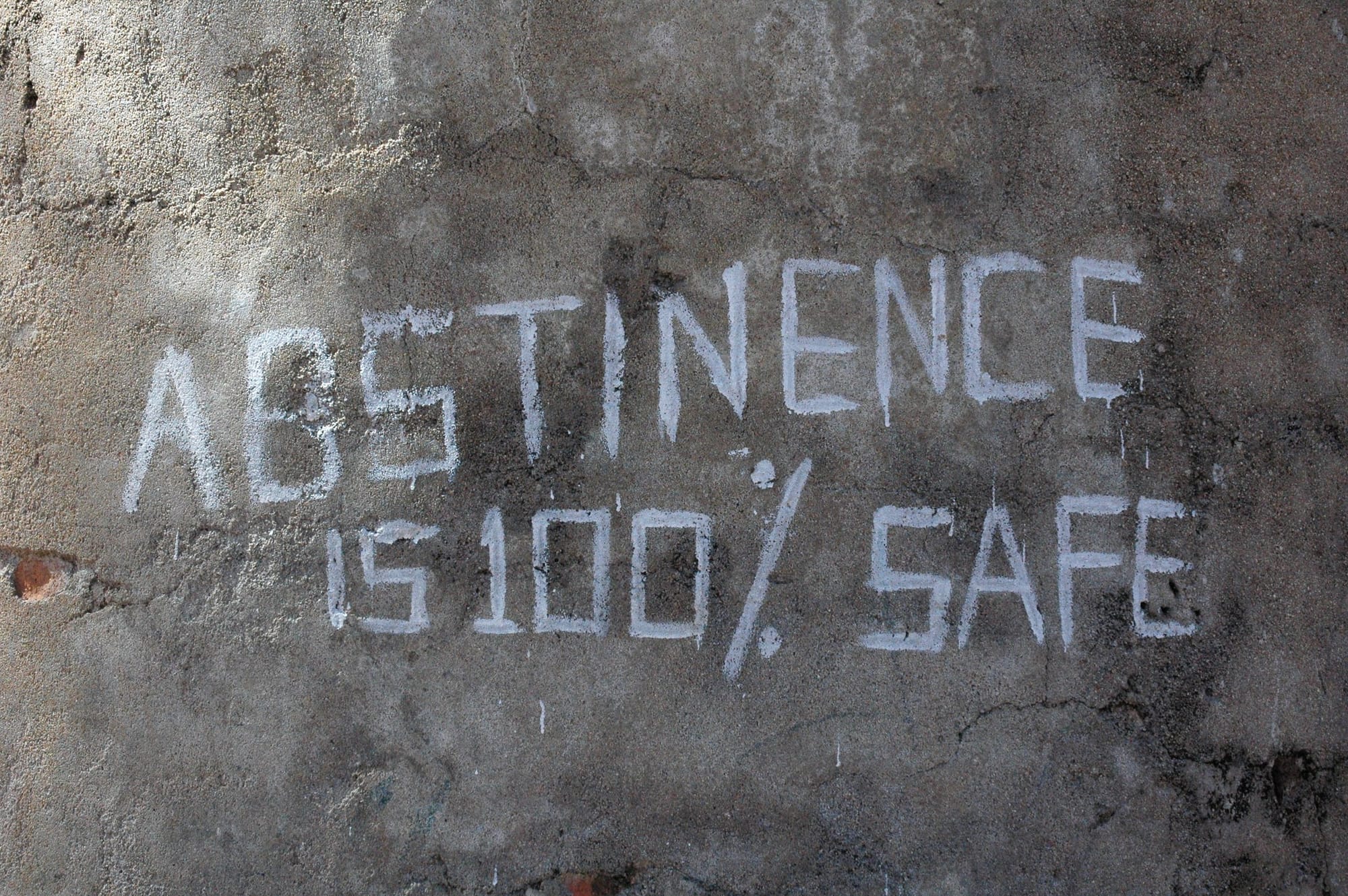

Harm reduction is a spectrum. It can be eating a granola bar and hydrating before drinking or using drugs, testing for xylazine or using sterile syringes. And, while it can be a way to keep someone alive until they opt to remain abstinent — this phrasing is often an effective way of selling the general public on harm reduction — dismissing it as just that ignores the plethora of literature documenting its efficacy in improving people's lives by allowing them to make healthier choices.

Sobriety, on the other hand, is more straightforward. Either you are, or you aren't.

Abstinence-based treatment for those with substance use disorder can play a critical role in public health and undoubtedly has saved countless lives, but programs predicated on abstinence also fail to meet people where they are by only offering something that someone either isn't ready for or does not want at all. (Disclaimer: I'm an individual in abstinence-based recovery).

They also borrow from the drug-war playbook.

Traditional treatment programs, of which there are many in Baltimore, typically rely on punitive measures if someone uses drugs. A "relapse," for instance, often is met with immediate discharge from a program.

The expectation of sobriety extends far beyond just treatment in U.S. culture and public policy. Even some government programs, such as those that provide housing, can upend people's lives by refusing or taking away services if someone doesn't abstain from substances. Prisons, employers and other areas in which there is a power dynamic also require abstinence — likely a result of stigma that considers drug use a moral failing.

As evidenced by city council hearings, there is a dissonance among those who legislative in City Hall and the people in Mayor Brandon Scott's administration tasked with leading the city's overdose crisis response.

Sara Whaley, executive director of the Mayor's Office of Overdose Response, said that the administration's focus will ensure it advocates for "approaches and policies that meet residents impacted by substance use where they are."

"By definition, harm reduction is about reducing the harms associated with high risk activities — this can include sterile drug use equipment, naloxone, and referrals to services including treatment. For some, harm reduction can lead to treatment and long-term recovery. As the Mayor often says, the first thing needed to receive treatment is to still be alive. Overall, we have a responsibility to continue supporting all residents regardless of whether they eventually seek treatment or are abstinent."

Even if council members don't share that outlook and instead aim to end addiction or reach 100% treatment rates, it would be impossible. Addiction will exist as long as human biology and autonomy do, and abstinence is neither something everyone can nor should be expected to attain.

Though studies have shown the vast majority of people who use drugs do not develop SUD, the population that was discussed at this week's hearings is quite large.

Jennifer Martin, deputy commissioner of the Baltimore City Health Department Division of Population Health and Disease Prevention, said at one of this week's hearings that the health department in the past has estimated as many as 25,000 residents have SUD.

"Estimating is challenging... I'm not sure that I'm completely confident in that today," Martin said.

There are other estimates out there, at least for opioid use disorder.

During oral arguments in Baltimore's landmark opioid trial last year, expert witnesses used a statistical model to estimate that 32,500 residents at any given time have OUD. As much as 6% of the city's population, then, is living with addiction. And every one of those individuals deserves quality treatment — if that's what they want.

Yet as that conversation unfolded this past month, the same people who complained about an apparent influx of inadequate treatment programs have been the same individuals who oppose new methadone clinics in their neighborhoods.

So, if the best interests of drug users are actually in officials' and residents' minds as they discuss a response to the overdose crisis, they must be consistent.

If Baltimoreans demand access to high-quality treatment programs, they must also demand access to high-quality harm reduction programs for those who continue to use drugs — without expectations of sobriety.

These things aren't mutually exclusive; they are both critical to keep people alive.

Early on in the U.S. harm reduction movement, which began in the 1980s in response to the AIDS epidemic, the ideology often clashed with those who abided by the more traditionalist approach to drug treatment. The main argument, which remains prevalent today, is that harm reduction enabled drug users rather than helped them.

The two approaches coexist much more peacefully today as research repeatedly vindicates the harm reduction approach, but Baltimore's discourse surrounding drug use demonstrates that the decades-old tension continues to exist.

One way to look at things is that there has historically been three approaches to drug use: harm reduction, abstinence-based treatment and punishment.

"This is a complex, challenging thing to wrap our arms around," said Council President Zeke Cohen at a hearing about treatment programs this week.

"This is about businesses that are established to help people in our most vulnerable state to get treatment and recovery, which we know is the answer. We tried the War on Drugs and failed. We know we cannot incarcerate our way out of this issue."

Though Cohen's comments about the failure of the drug war are welcome, they do not reflect the realities of drug policy in Baltimore.

Baltimore officials, including the Baltimore Police Department under Scott's leadership, are actively employing drug-war tactics as they make poignant statements at public hearings about the overdose crisis. Even in those settings in which they retain control over much of the discussion, even some of the rhetoric they use has actively advanced stigma about those who use drugs.

It's a dangerous path. And as council members, the media and the public hyperfocus on treatment, it can overshadow discussions about the need to address root causes of drugs use such as poverty, housing, and education.

"Factors that support long term recovery like stable housing and employment are also protective factors that can prevent substance use from turning into a substance use disorder, or can assist in stabilizing someone in chaotic use," Whaley noted.

This past month has brought a level of transparency and public discourse about Baltimore's overdose crisis that we haven't seen in a very long time. It followed more than a year of relative silence among city officials, who insisted the crisis is an important issue while using litigation as a shield to avoid talking about how they would address it.

Yet that public discourse means nothing if the officials leading those conversations and creating drug policies maintain a narrow-minded view of how to best serve those who use drugs in Baltimore.

Miss last week's newsletter? You'll want to check it out

After a mass overdose event in West Baltimore earlier this month, the importance of harm reduction — and the failures of prohibition — were as clear as a summer day. Yet in the following weeks, city leaders have instead joined President Donald Trump in doubling down on a police-led response that could spell death for drug users and fuel mass incarceration.

Not long after the Republican president augmented his assault on public health by signing a bill expanding mandatory minimums for those distributing fentanyl analogs, Mayor Brandon Scott made it clear he'd borrow from the bipartisan drug-war playbook. On Wednesday, the Democrat announced the expansion of the city's Group Violence Reduction Strategy to the Baltimore Police Department's Southern District, giving more reach to a program that has served as a vehicle for drug crackdowns under the guise of violence prevention for years.

Read the full newsletter here.

Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data has been updated with the latest local, state and national data

Baltimore's overdose death toll in 2024 has increased to 777 — this is preliminary data that's subject to change as causes of death are determined. That marks a nearly 26% decrease from the year prior.

In the 12-month period ending in June, Baltimore saw 586 deaths, a death rate of 100 per 100,000 people. Statewide, there were 1,360 deaths, a death rate of 22 per 100,000 people.

The data indicates that fatal overdoses continue to trend downward after years of climbing, though poor Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore continue to suffer the most.

Check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard here.

Click here to learn more about harm reduction resources in the Baltimore area.

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: "In the Face of a Volatile Drug Supply, People Take Harm Reduction Into Their Own Hands"

A new study from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health sheds light on how people who inject drugs (PWID) are responding to the growing instability and danger in the U.S. illicit drug supply. Despite facing structural vulnerabilities, participants in the study demonstrated a keen awareness of changes in drug quality and content, and many are taking proactive steps to reduce their risk of overdose, injury, and other harms.

Published July 24, 2025 in the journal Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, the qualitative study explores the experiences of 23 PWID in Baltimore City, where a growing number of opioid-related deaths and the emergence of new, harmful adulterants like xylazine have made drug use increasingly perilous. Participants reported encountering potent and unpredictable drug combinations and described cognitive, behavioral, and social strategies they use to navigate this new reality. Notably, the paper’s publication comes just two weeks after a mass overdose in Baltimore’s Penn North neighborhood sent dozens of people to the hospital in the span of a few hours and tests revealed unfamiliar ingredients.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments