The Maryland Department of Health has scrubbed any mention of “harm reduction” from the state’s leading grant program for organizations that provide care to people who use drugs. The move raises questions about whether it’s a pragmatic terminology shift to guard against federal threats, or outright capitulation to the federal government’s assault on public health.

The “Advancing Cross-Cutting Engagement and Service Strategies for People who Use Drugs” program, known as ACCESS, made history in 2020 as the first in the state to provide funding directly to harm reduction organizations.

Years later, as President Donald Trump’s administration ramps up its drug war and slashes funding that’s crucial to prevent overdose deaths, the latest request for applications (RFA) from the Maryland health department’s Office of Harm Reduction—which gives little time for organizations to adjust their own language when they apply—has dropped the name of the movement from which the office takes its title.

This follows open hostility to harm reduction from the Trump administration, as demonstrated by a July “Dear Colleague” letter, which stated that Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) funds “will no longer be used to support poorly defined so-called ‘harm reduction’ activities.”

“In my opinion, Maryland is taking [federal guidance] to an extreme,” Erin Russell, a harm reduction consultant who started the ACCESS program while chief of the former Center for Harm Reduction Services, told Filter.

“I think these are unspoken messages about what their leadership’s opinion is on harm reduction,” she said of the Maryland administration. “They’re not being transparent about the funding amount, and they’re not supporting the team by producing a transparent and normal RFA process. The scrubbing of harm reduction is not coming from the harm reduction team themselves, so we can only assume that someone higher up is parsing this change.”

Funding for ACCESS grants has been made up of both state and federal dollars. A state health department spokesperson told Filter that the program allocated a total of $26 million in the most recent fiscal year, but declined to comment when asked about the next budget allocation and whether there would be cuts.

The program has been responsible for allocating millions to local harm reduction organizations annually, and there are fears that there will be a significant decline in grant funding for the upcoming fiscal year.

The ACCESS RFA opened on December 22, and will close on January 22. The state health department says the timeframe exceeds the three-week minimum for notices required under state law. But Russell called the timeframe “absurd.”

The request was issued over the holiday season, she noted, giving organizations even less time to apply for funds when they will likely have to modify their application language to do so.

The terminology change in the RFA, which replaces “harm reduction” with phrases such as “services designed to reduce morbidity and mortality among people who use drugs,” isn’t in and of itself the problem, Russel said. Regardless of what compassionate care for people who use drugs is called, the movement will go on, and life-saving services will continue.

However, the move, combined with actions at the federal level, has negative implications for local harm reduction initiatives. Not only could they receive less aid because the grant program itself is underfunded, but they could be pushed further underground.

“I don’t think the work will continue at the same volume that it is now, or has been,” Russell said. “There are plenty of programs that were maybe renting space and offering drop-in services that are not going to move back to the trunk of someone’s car. Or places that were going to buy mobile vans are now not going to do that level of expansion.”

“It hurts people,” Russell said, “and more people will die with the system as it’s been redefined.”

In July, Trump signed an executive order in July to criminalize homelessness, ramp up forced institutionalization of people with mental illnesses and substance use disorders, and defund life-saving harm reduction programs. The SAMHSA letter, stating that certain harm reduction programs "only facilitate illegal drug use and its attendant harm," followed days later.

Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Filter that a shift in how the Maryland government speaks about harm reduction may be a necessary hardship under the Trump administration.

“For people who understand and practice [harm reduction], hearing the words vilified is unpleasant—that’s the minimum,” Sharfstein said. “It’s very frustrating. It’s unfortunate, but in the end, I think this is a compromise that they may need to make to be able to provide services that really do save people’s lives.”

It’s unclear what policy impact these changes will have, he added, as the federal government seems to have thus far equated harm reduction with programs such as overdose prevention centers, of which there are only three sanctioned examples in the country.

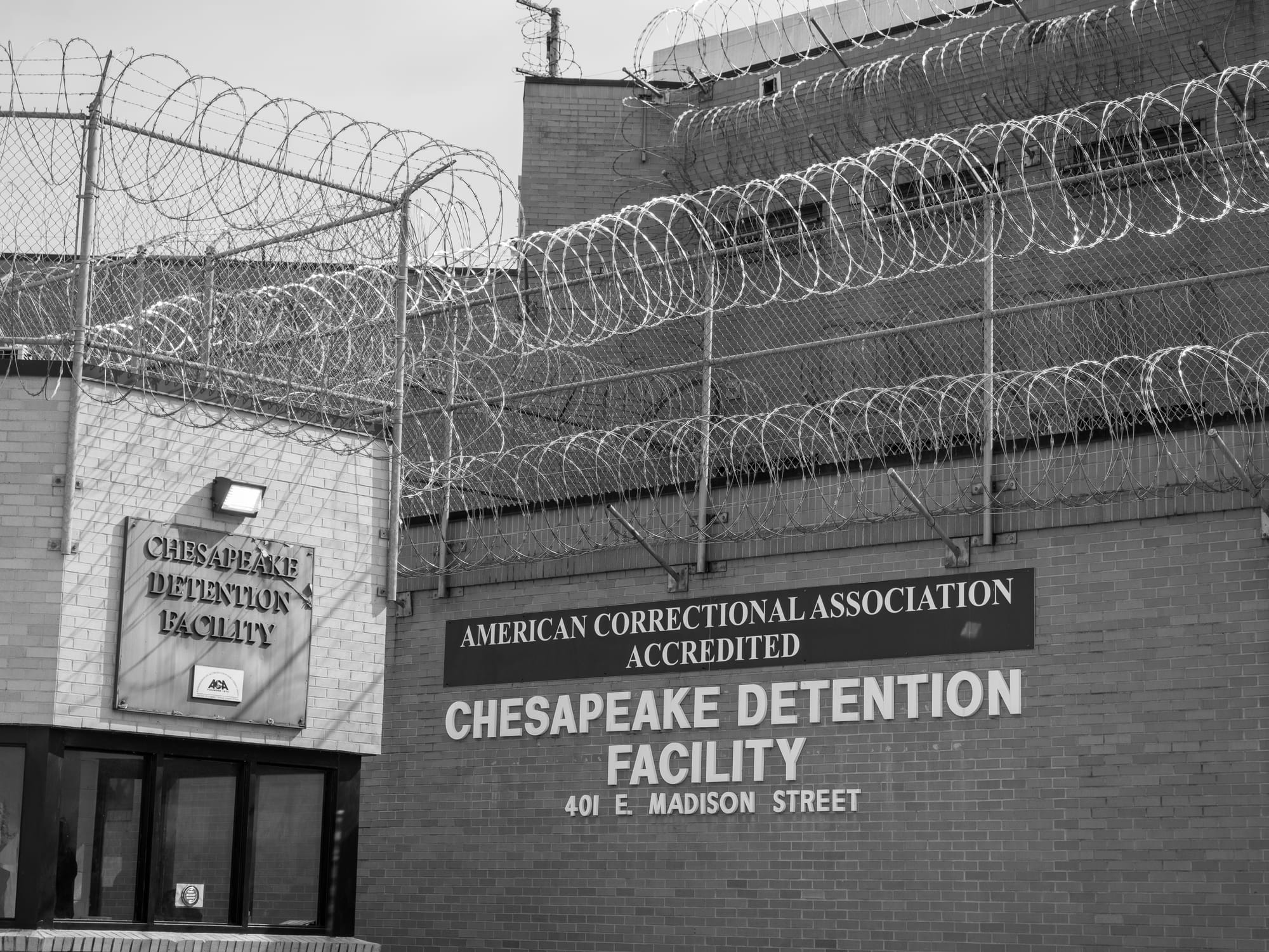

In Baltimore, where OPC have been debated for years as the city’s fatal overdose rate climbed to the highest in the nation, the federal guidance has already been felt on that front.

In October, Baltimore Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Taylor told Filter that the city wouldn’t pursue these life-saving spaces because of fears of losing federal funding.

More recently, Mayor Brandon Scott (D) removed OPC from his list of legislative priorities. And members of the state’s Harm Reduction Standing Advisory Committee announced in December that OPC legislation wouldn’t be introduced in the upcoming state General Assembly session, as they will instead channel their energy into decriminalizing drug “paraphernalia.”

Still, state officials have insisted that existing programming will not suffer. Health Department spokesperson David McCallister told Filter that the agency is simply adjusting its language to abide by guidance from the Trump administration.

“This funding, along with state funds and other federal grants, is critical to our mission of continuing life-saving, evidence-based interventions for Marylanders who use drugs,” he said. “The Maryland Department of Health remains focused on protecting the health and safety of our communities, which includes addressing the health, well-being and mortality of Marylanders who use drugs.”

The state likely cannot afford to have its harm reduction efforts take a hit. Its overdose prevention initiatives have contributed to a notable decline in deaths statewide. In Baltimore, which has by far the highest fatal overdose rate in the state, there were 777 overdose deaths in 2024, a historic 25.5-percent decrease from the year prior, according to preliminary data.

In the 12-month period ending in October, the most recent data available, Baltimore saw 560 deaths, indicating that the trend continued into much of 2025.

Update, January 13: This article was updated to reflect information about the last ACCESS budget allocation, received from the Maryland Department of Health after publication time.

Comments