It's been six weeks since a mass overdose event in Penn North prompted police raids and sensationalized media coverage, bringing Baltimore's overdose crisis — and drug war — back into the spotlight.

Yet new data from the Maryland Department of Health shows that the prevalence of what drove the overdoses may have been overblown in the midst of cop crackdowns, and fatal overdoses in the city continue to decline. As evidenced by the department's Rapid Analysis of Drugs program, the leading drug-testing initiative in the state, the potent benzodiazepine cited in reports was not only an outlier because of its rarity but also the sheer amount of it that was in the batch.

"Two syringe samples from the area produced the following results: acetaminophen, caffeine, fentanyl, N-Methylclonazepam, and quinine," stated the most recent quarterly report, published last week.

"N-Methylclonazepam is a benzodiazepine derivative with intense sedative effects and based on the lab testing from NIST, there was approximately 10 times more N-Methylclonazepam than fentanyl in these samples. Based on other samples NIST has analyzed, benzodiazepines typically make up a smaller percentage of the sample than fentanyl or other opioids."

Benzodiazepines, which have been around for decades, can increase the likelihood of overdoses because of their depressant properties and complicate prevention efforts, as they are resistant to naloxone.

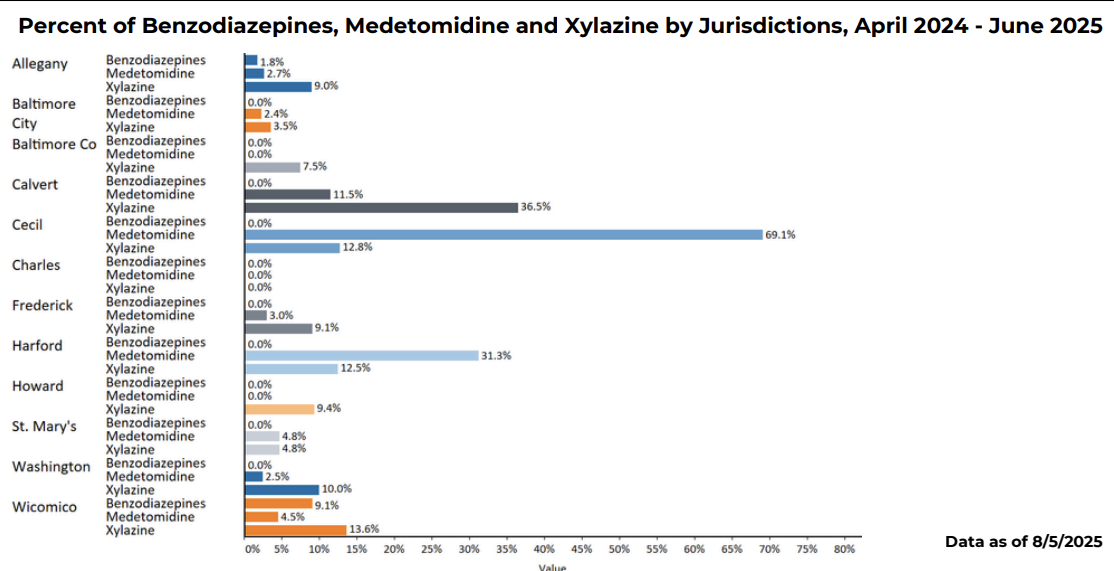

The drugs, however, appear to be incredibly rare in Baltimore's drug supply. Between April of last year and June of this year — before the July 10 event in Penn North — no drug samples in the city contained a benzodiazepine, according to the RAD report.

Only two of the 12 counties whose syringe service programs provided samples to the state contained the adulterant, with more than 9% of Wicomico County's samples testing positive. The variation speaks to the unpredictability and lethality of the unregulated drug market, which shifts in an increasingly dangerous direction as cops carry out drug busts and other enforcement measures.

That said, though nearly 30 people were hospitalized on that tragic day, no one died.

That fact can undoubtedly be attributed to harm reduction workers who rapidly distributed naloxone and other supplies. They also conducted targeted outreach well after the incident, offering a prime example of why compassionate care for drug users is so important.

Unfortunately, media coverage of the event and comments by public officials quickly shifted to interdiction rather than a full-on public health response, feeding a narrative that has long fueled the War on Drugs.

As news outlets highlighted copaganda from the Baltimore Police Department's top brass, its Group Violence Unit and plainclothes District Action Teams raided the area, arresting five people on drug charges around the corner from the spate of overdoses.

The BPD's presence was part of a familiar framing in which officials made a call to action to catch the "bad guys" who distributed the drugs, contributing to the moral panic that ensued.

Mayor Brandon Scott could have issued an emergency declaration to open overdose prevention centers and save lives. Instead, city officials and the cops fostered an environment of fear with the help of media coverage that parroted their calls for arrests.

Based on the widespread response, no one would ever know that fatal overdoses are on the decline.

Recently published preliminary data from the state health department show that, in the 12-month period ending in July, Baltimore saw 563 deaths, a death rate of 96.1 per 100,000 people.

That death rate is nearly half the death rate that Baltimore experienced during its peak in 2021 — a similar death rate was also seen in 2023 — and it demonstrates that deaths have continued to decline since the city saw a historic 25.4% decrease in fatalities last year.

Though the 778 deaths last year marked the lowest death toll since 2017, the number also proves that innumerable preventable deaths remain in Baltimore, and the overdose crisis continues to take the lives of an astronomical number of people.

The data is far from a reason to be complacent, and it's absolutely not the time to push drug users to riskier sources through drug busts and other crackdowns. Prohibitionist responses to drugs have been proven to increase fatal overdose rates and contribute to violent crime, unlike what local officials have repeatedly argued.

The irony behind the response to the mass overdose event is that it distracts from more pressing issues related to the drug supply, which becomes more lethal and unpredictable in direct response to the same efforts that the city employed that day.

A significantly more pressing threat is medetomidine, a potent veterinary sedative. The drug has begun to replace xylazine, another sedative that prompted concerns nationwide both for its resistance to naloxone and the fact that it can cause severe ulcers, abscesses, and infections.

Just 2.4% of drug samples in Baltimore contained medetomidine between April 2024 and June of this year, while 3.5% contained xylazine in Baltimore.

Although RAD suffers from relatively small sample sizes, the quarterly report notes that the former is becoming increasingly common while the latter is becoming rarer. Statewide, about 9% of samples contained medetomidine, slightly more than the roughly 8.5% that contained xylazine.

The reason for the rise of medetomidine is fairly straightforward: prohibition.

Take, for example, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro signed a law last year classifying xylazine as a Schedule III drug after the state temporarily did so the year prior. Subsequently, medetomidine replaced it as the most common adulterant in Philadelphia, one of the cities hit hardest by the overdose crisis.

Crack down hard, face the consequences. The street drug economy can adjust, and it will do so in a deadly manner.

Similar efforts have surfaced in Maryland but failed, with the state health department acknowledging the dangers of beefing up regulations. Despite this, the BPD's drug enforcement efforts, which drive Baltimore's drug war, remain a vessel to enforce prohibition, contribute to mass incarceration and, ultimately, get drug users killed.

The suits and ties in City Hall don't seem to recognize that as Baltimore's drug supply shifts, so should the dollar signs.

The city recently accepted a deal that will net it just $580 million of the billions of dollars it had sought to combat the overdose crisis. That is less than the BPD's annual budget, and it is to be spread out over 15 years.

As the city's overdose death toll continues to dwarf that of homicides, a prudent and targeted allocation of resources is more important than ever.

Pour money into harm reduction programs. Unilaterally allow for overdose prevention centers. And perhaps most importantly, stop signing blank checks to feed a police department that's carrying out a drug war and getting drug users killed.

Miss last week's newsletter? You'll want to check it out

With Baltimore accepting an offer that represented a massive blow to its efforts to combat the overdose crisis, the city's landmark opioid case seems to have finally come to an end.

On Thursday, the city accepted Baltimore City Circuit Court Judge Lawrence P. Fletcher-Hill’s $152 million proposal in the case against McKesson and Cencora, formerly AmerisourceBergen. While appeals are still possible, it could mark the end of a legal saga in which Baltimore sought as much money as possible to augment its harm reduction and treatment initiatives — one that will now bring the city a total of $580 million to its coffers when factoring in a handful of previous settlements.

“Generations of Baltimoreans have lost loved ones to substance use as a direct result of the opioids that Big Pharma pushed on our neighborhoods," Mayor Brandon Scott said in a statement. "While no amount of money can ever undo that harm, this award will help us expand our recovery programs, prevent future overdose deaths, and finally break the cycle of substance abuse in Baltimore."

Read the full newsletter here.

Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data has been updated with the latest local, state and national data

Baltimore's overdose death toll in 2024 has increased to 778 — this is preliminary data that's subject to change as causes of death are determined. That marks a 25.4% decrease from the year prior.

In the 12-month period ending in July, Baltimore saw 563 deaths, a death rate of 96.1 per 100,000 people. Statewide, there were 1,338 deaths, a death rate of 21.7 per 100,000 people.

The data indicates that fatal overdoses continue to trend downward after years of climbing, though poor Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore continue to suffer the most.

Check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard here.

Click here to learn more about harm reduction resources in the Baltimore area.

Filter: "Tennessee Harm Reductionist Faces Charges for Drug Checking"

A constant threat to harm reductionists is that without clear legal protections, their lifesaving work can be criminalized. The recent arrest of a Tennessee researcher and outreach worker, who was engaged in drug checking, drives home the reality of that threat.

Dr. Paige Lemen is a recent PhD graduate in biomedical sciences at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and co-founder of 901 Harm Reduction, a Memphis-based group providing supplies and resources. She was arrested while transporting a 0.7-gram drug sample for laboratory testing, and now faces a series of charges—including possession with intent to sell, possession of drugs not prescribed, and driving under the influence of a controlled substance. The charges have troubling implications for future harm reduction work.

The arrest occurred on June 3 in Jackson, Tennessee, a small city near Memphis. Minutes earlier, Lemen had picked up the small drug sample for lab testing, something she had routinely done before. She believed at the time that the powdered sample was most likely to contain fentanyl.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments