In Baltimore and cities across the country, open-air drug markets are often referred to as a "public nuisance" — a plague that hurts local businesses, strikes fear into residents and serves as a catalyst for violence.

However, whether it be neighborhoods such as Kensington in Philadelphia or Penn North and Lexington Market in Baltimore, they didn't appear out of thin air. Rather, they've existed for decades as a manifestation of systemic oppression, the failed War on Drugs and the abandonment of communities. At a Baltimore City Council Public Safety Committee hearing on Tuesday, frustration ensued when there seemed to be no consensus on how to rebuild these areas.

"We've seen very significant declines in violence, and this is one of those quality of life issues that I think folks want to resolve," said Councilman Mark Conway, who chairs the committee. "But I think the way we have historically looked at it… The problem has been primarily enforcement-based, and if we know anything about this issue, enforcement alone is not necessarily going to solve it.”

"It's not okay for us not to have a plan."

Conway's comments came before local law enforcement officials and members of the mayor's administration as they discussed the city's progress in addressing crime. During the discussion, officials touted statistics that prompted myriad news articles earlier this year: Baltimore saw the lowest murder rate since 2015 and, at 201 homicides, there was a 23% decrease from the year prior, they said.

However, when it comes to drug enforcement — which they seem to consider a key tenet in violence reduction efforts — council members said their constituents haven't felt much relief.

As is typical in such discussions, officials talked of residents who feel unsafe in their neighborhoods. They're too frightened to venture onto the streets, where dealers are hawking their products and others are using them — the most common of which are fentanyl and crack cocaine.

As for many of those participating in the activities, however, it's out of necessity; the markets are concentrated in high-poverty areas that have experienced debilitating disinvestment, leaving many to resort to selling drugs to either support their families or feed addictions that often can be traced back to generational trauma.

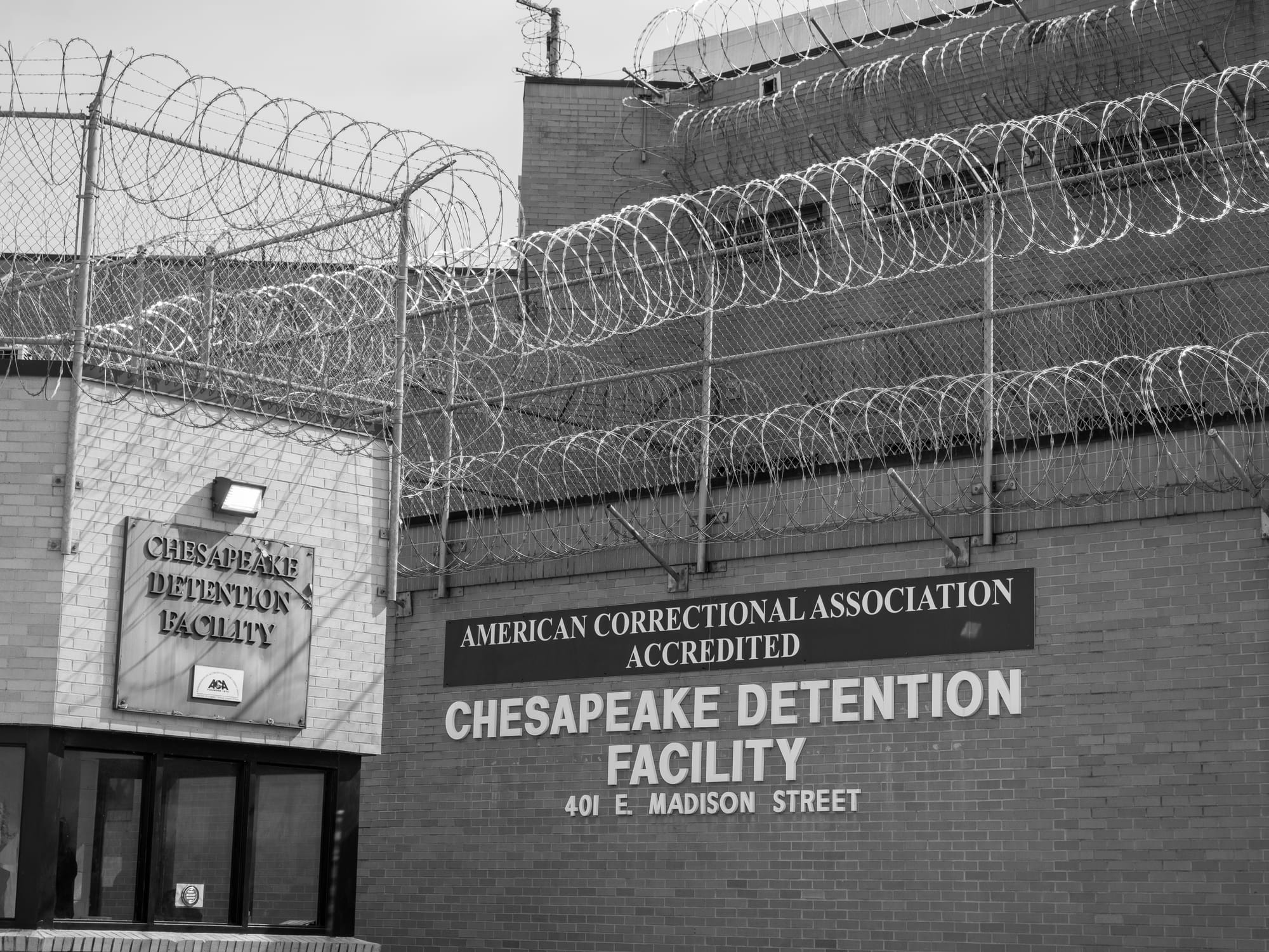

Historically, the War on Drugs has demanded a heavy-handed response to these "public nuisances" — one that is racist at its core. Black people are both arrested and incarcerated at higher rates than other groups for drug-related "crimes," and they have been portrayed as violent, dangerous criminals in the decades-long war. In practice, cities' responses have facilitated mass incarceration, with the first arrest kickstarting a carceral cycle that is detrimental to the livelihoods of its victims.

Law enforcement officials on Tuesday stressed that they are indeed enforcing the laws on the books. There have been 360 drug-related arrests this year, they said. That's about a 12% increase since this time last year. Of that, 277 were felonies and 133 were misdemeanors, the highest concentration of which took place in the western district and central district, respectively.

The efforts come as State's Attorney Ivan Bates has reintroduced the prosecution of low-level drug crimes, reversing a policy created by his predecessor and bringing "broken-windows" policing back into the spotlight.

Yet the police seemed to acknowledge that arresting drug users and dealers is not the only solution — whether it's a solution at all is up for debate — in attempts to address high-traffic drug areas. As evidenced by the fact the police department's budget is nearly $600 million and these issues remain so pervasive, that may seem like common sense.

“The persistent challenges of open-air drug markets in Baltimore demand a multifaceted strategy, one that integrates enforcement, harm reduction, public health interventions and economic development,” said Deputy Police Commissioner Kevin Jones. "BPD has a range of targeted strategic enforcement strategies to disrupt and dismantle these drug activities, whether through the first layer of patrol all the way up to our GVRS model, where we're going after drug trafficking and organizations and group member-involved incidents."

Jones' comments indicated the city at least somewhat understands the depth of the issue. The same was evident in remarks from Ty'lor Schnella, the mayor's local affairs liaison.

"Enforcement alone won't solve this problem," Schnella said. "That's why Mayor Scott remains committed to strategic long-term investments such as reducing vacant properties, expanding housing assistance, creating job opportunities and job training and increasing recreational opportunities for our young people and families through coordinated efforts with city agencies."

Hearing officials mention the importance of harm reduction and community-building as they look to address drug markets is somewhat encouraging. As history has taught us, systemic issues necessitate systemic reforms, whether those manifest in policies that address poverty, housing insecurity or health disparities.

Yet the only data officials provided on Tuesday to demonstrate the city's response covered arrests — a potential indicator of where their true priorities lie.

In discussions about drug enforcement, there is consensus among city officials that these drug markets must be addressed for violence prevention efforts. Studies have indeed shown that the illicit drug trade is linked to increased violence, though the reason for the correlation has been debated.

However, increasing policing may not have the intended effect. In fact, it may have the opposite impact, as evidenced by a 2011 study in the International Journal of Drug Policy.

"The results of this systematic review suggest that an increase in drug law enforcement interventions to disrupt drug markets is unlikely to reduce drug market violence," the study found. "Instead, from an evidence-based public policy perspective and based on several decades of available data, the existing scientific evidence suggests drug law enforcement contributes to gun violence and high homicide rates and that increasingly sophisticated methods of disrupting organizations involved in drug distribution could paradoxically increase violence. In this context, and since drug prohibition has not achieved its stated goals of reducing drug supply, alternative regulatory models for drug control will be required if drug market violence is to be substantially reduced."

I've spent quite a bit of time in Penn North and Lexington Market, both to buy drugs and write stories (not at the same time, of course). Not once did I feel unsafe. To me, it simply felt like I was in the midst of people who lived a lifestyle necessitated by their circumstances — one that helped keep them alive in a capitalist society where drugs can be both moneymakers and a reprieve from trauma. Some were selling, others were buying.

The commonality: They were put in this position. Not by bad decisions, but by a mandate created by oppression.

And where are the police as these drug deals occur? At first glance, the environment resembles a surveillance state, with the city's most disenfranchised being watched as if they were on a television screen.

In Penn North, dozens of cops sit quietly in their cars on street corners watching it all unfold. Law enforcement's response does not indicate an aggressive, "jump-out" approach like has been seen in the past — though the police have made clear they're still slapping handcuffs on residents. If there have been increased investments in compassionate community-building initiatives, though, they aren't very apparent.

I recently spoke with Catherine Tomko, a social scientist focusing on substance use and mental health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. To describe modern-day policing in Baltimore, she invoked the "inflection point" of the Baltimore Uprising in response to the death of Freddie Gray.

The debacle uncovered "egregious, racist" policing practices in Baltimore, Tomko said. She also very explicitly described how those practices, a key weapon in the War on Drugs, decimate communities of color.

"Once someone is arrested, even if they don't go on to be convicted or sentenced or incarcerated, there's big interruptions in their life, so that could mean disruptions in childcare, employment and family. With a lot of folks who are arrested for possession, if you're using buprenorphine or something to manage your opioid addiction, you're not guaranteed that in prison necessarily. So that all right there is destabilizing, even in the short term. But then, in the long term, people who are incarcerated for drug possessions, especially federal charges, are systematically excluded from a lot of social programs."

It's clear Baltimore's policing strategies don't inspire confidence among those who are familiar with the history of U.S. drug policy and local enforcement efforts. Yet regardless of race, drug users themselves are often discriminated against for what many consider a moral failing.

Freshman Councilman Zac Blanchard, vice chair of the Public Safety Committee, made a notable comment about drug enforcement that related to this during Tuesday's hearing.

“[The response to] open-air drug markets shouldn’t be interpreted in any way as an interest in criminalizing addiction," Blanchard said.

As the city looks to combat the drug markets, however, the "appearance" of its response isn't the issue. It's how the city responds in practice — which seems to focus on interdiction in the name of violence prevention.

The city will be given an opportunity to expand its response to a more holistic, evidenced-based and compassion-driven approach to drug policy with the help of a windfall of opioid restitution funds. Hundreds of millions of dollars are slated to hit the city's coffers by the end of the year, and the unprecedented amount of money could provide an unprecedented opportunity to reverse its current trajectory.

The mayor's office is expected to unveil more details of how it plans to respond to drug markets in the coming weeks. We will see where its priorities lie, at least on paper.

Earlier this week, I asked for a gift: your support. It's essential to keep doing what I'm doing, and I'm thankful for those who already read my work.

Today is my 29th birthday and, to be honest, I didn't think I'd make it this far — I thought drugs and alcohol would have taken me out quite a while ago.

However, I'm still here, and I don't necessarily have plans to stop doing this anytime soon (both living and writing this newsletter, that is). In light of this, I have a question: Would you support Mobtown Redux?

If you're reading this, you're already doing something to support my work. And if you're a subscriber, whether free or paid, I'm grateful to have you onboard. But with this publication still being relatively new, I thought I'd still reach out.

There are multiple ways you could continue to show support for Mobtown Redux. You could upgrade to a paid subscription, donate or continue to read my work and share it with others.

Fentanyl overdoses are down in every state, NPR reports

The deadliest phase of the street fentanyl crisis appears to have ended, as drug deaths continue to drop at an unprecedented pace. For the first time, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have now seen at least some recovery.

A new analysis of U.S. overdose data conducted by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill also found that the decline in deaths began much earlier than once understood, suggesting improvements may be sustainable.

"This is not a blip. We are on track to return to levels of [fatal] overdose before fentanyl emerged," said Nabarun Dasgupta, lead researcher on the project, which examined overdose records from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read the full article here. For local data, check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard.

Check out the harm reduction bills in the General Assembly I'm keeping an eye on; legislation marked with asterisks is unfavorable in the eyes of harm reductionists.

"Crossover Day" is Monday. It's the deadline by which bills have to pass in one of the chambers of the General Assembly to be guaranteed consideration in the other. As it now stands, all of these bills are sitting in committee without a vote scheduled — a potential indicator that key harm reduction efforts could die in committee this session. Check them out below:

- Senate Bill 83, sponsored by Sen. Shelly Hettleman, D-Baltimore County. This bill would legalize overdose prevention centers (OPCs) in Maryland, allowing for up to six programs statewide. The bill is awaiting a vote in the Senate Finance Committee. Previous iterations of the bill have repeatedly died in committee over the years.

- House Bill 845, sponsored by Del. Joseline Pena-Melnyk, D-Prince George's, and numerous other delegates. This is the companion bill to SB83 and is awaiting a vote in the House Health and Government Operations Committee.

- Senate Bill 370, sponsored by Sen. Cory McCray, D-Baltimore City. This bill would decriminalize drug paraphernalia statewide. Both chambers passed a different iteration of this legislation in 2021 before it was vetoed by failed U.S. Senate candidate and former Gov. Larry Hogan. The new bill is awaiting a vote in the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee.

- House Bill 556, sponsored by Del. Karen Simpson, D-Frederick, and a few other delegates. This is the companion bill to SB370, and it's awaiting a vote in the House Judiciary Committee.

- *Senate Bill 604, sponsored by Del. Jeff Waldstreicher, D-Montgomery, and Del. Justin Ready, R-Frederick. This bill would create a maximum prison sentence of 20 years for people who distribute fentanyl or heroin resulting in death, also known as "drug-induced homicide." Paired with legislation passed in 2017 that increased the maximum sentence for fentanyl dealers to 30 years, harm reductionists say the bill could lead to sentences as long as half a century. The bill is awaiting a vote in the Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee.

- *House Bill 1398, sponsored by Del. Chris Tomlinson, R-Frederick, and numerous other delegates. This is a companion bill to SB604, and it is awaiting a vote in the House Judiciary Committee.

Comments