Last week, nearly 2,000 harm reductionists from all over the world gathered in Detroit for the Reform Conference, an event dedicated to advancing a movement hellbent on saving the lives of those who use drugs.

The sea of people, reminiscent of a moshpit brimming with tattooed, drug-loving punks, converged at Huntington Place, a convention center along the Detroit River. Just across the body of water was Canada, which, just like the U.S., is witnessing an assault on compassionate care for drug users. For a moment, however, I felt a moment of respite from the chaos brought by the War on Drugs and its relentless grasp on communities in Baltimore and beyond. As I stood among the crowd, a powerful, euphoric sense of camaraderie came over me. It felt like home.

My work often feels like screaming into the void. But as I spoke with people hailing from places like Detroit, Portland and London, I recognized that people do, in fact, care about those who use drugs — and they care about them deeply.

But it wasn't long before the rose-tinted glasses fell off my face.

I soon felt the gravity of the moment, remembering that hundreds of my neighbors in Baltimore died preventable deaths last year alone. And, with tens of thousands more fatalities across the U.S., many in power are still out to destroy the one movement that's looking to put a stop to it all.

We've seen the drug war unfold in a way that hasn't been seen for decades. Amid deep cuts to public health funding, the authoritarian regime helming the White House has carried out numerous fatal military strikes against boats in the Pacific Ocean, baselessly claiming they'd been transporting drugs as tensions rise with Venezuela.

Republicans and Democrats alike have questioned or outright condemned the strikes. Yet, for decades, members of both parties at all levels of government have supported bloated police budgets that thrust their constituents – a disproportionate number of whom are Black – into jail cells or graves.

The drug war is a racist death campaign, and support for it crosses party lines.

Many Baltimoreans have seen the headlines about strikes on boats in an ocean far away, and they've drawn no connection to what's happening in Charm City. But that's a symptom of blissful ignorance we can't afford to have.

Like the cities from which other conference attendees came, a more than century-old campaign facilitated by fascist police forces, failed leadership and widespread contempt for drug users remains alive and well here, too.

It's just a different form of state violence, and the piecemeal reforms offered by those in power have done little to prevent blood from being shed.

On the first day of the conference, my phone blew up with notifications about the Baltimore Police Department raiding the Penn North neighborhood, where one month earlier, the third in a series of mass overdose events had occurred.

It wasn't the first raid, and it sure won't be the last. And as Police Commissioner Richard Worley has said himself, drug enforcement in Baltimore isn't just about those who sell them. Rather, there's "no way around" targeting drug users in efforts to crack down.

And the BPD's contributions to the drug war, which had led drug arrests to surge in tandem with the department's budget this year, has not only been encouraged by politicians, but it's also been fomented by local media.

News outlets have sensationalized the overdose crisis while parroting police talking points, failing to draw the connection between enforcement and overdose deaths. They've used their platforms to manufacture consent for the war, playing a key role in its proliferation by spreading disinformation about drugs themselves.

This is just the story of Baltimore, and it's not the only place experiencing this.

The suffering of our most vulnerable residents under the drug war and other forms of oppression is universal. Whether it be drug busts, the clearing of encampments or a budget that infuses more money into these actions, it's state-sponsored violence.

Last week, the people on the frontlines — the ones who see the impact on communities firsthand — made it clear they would not bend the knee to the government, both federal and local, as it infringes on human rights.

But it's also important to recognize there is, and must always be, a place in this space for drug users themselves. They are the ones who know what they need; they are the ones who know what we must do.

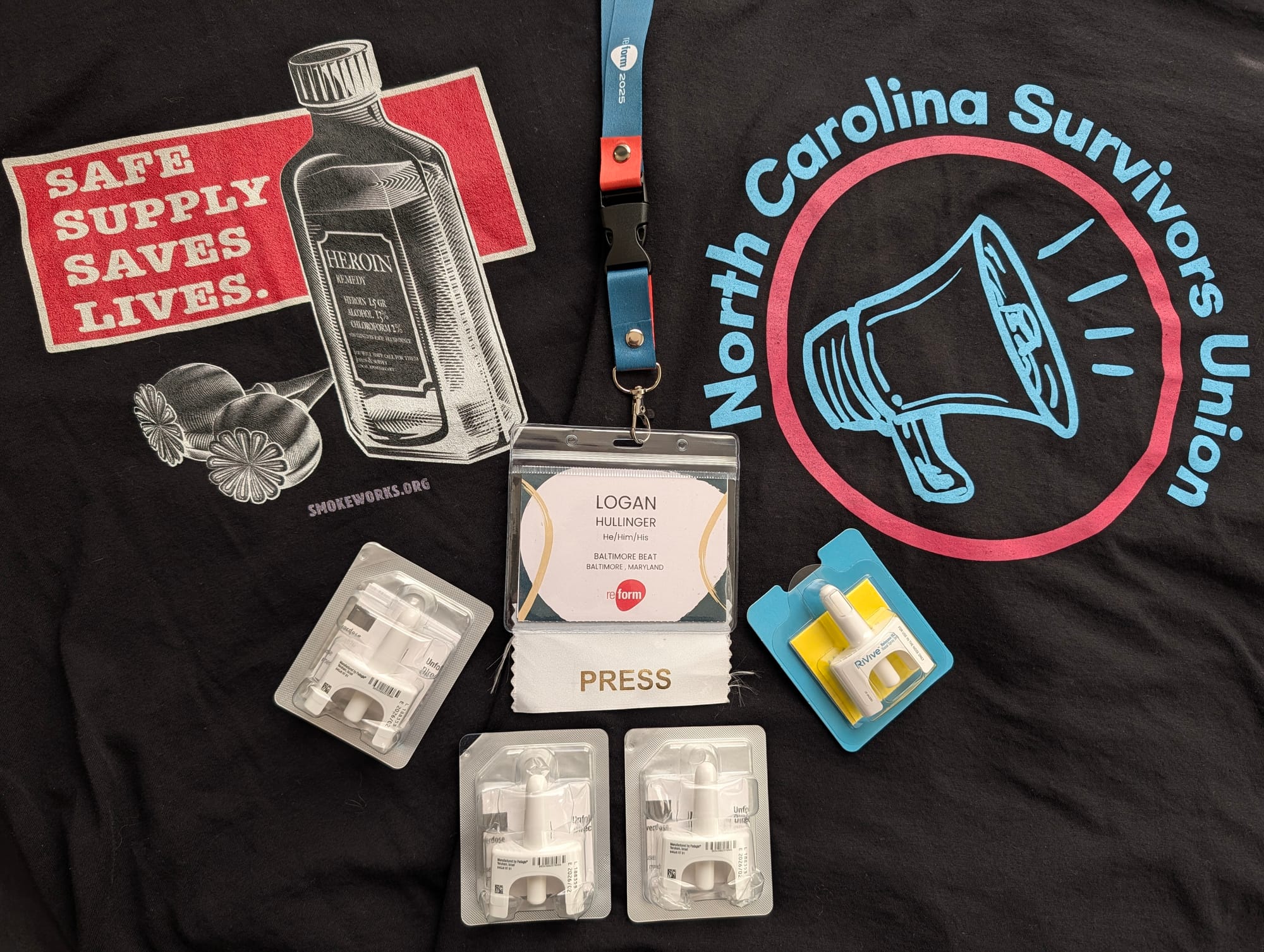

For some, they have one foot in advocacy, the other in drug use. As evidenced by organizations such as the National Survivors Union, they are uniquely positioned to continue building the movement.

As it now stands, the shadows are where many of those in power believe drug users belong. That sadistic view has not only denied people housing, education and other human rights, but also their lives.

But what would make many hopeless has emboldened harm reduction activists even more.

Many are still reeling from the loss of figures such as Louise Vincent, who helped build the North Carolina Survivors Union, and Peter Krykant, an activist who ran an unauthorized overdose prevention site from a van in Glasgow. Still, the people we've lost have energized a movement that will not stop until the drug war takes its final breath.

That's why the Reform Conference, where cool breezes off the Detroit River hit the faces of harm reductionists as they spoke of those who they've lost and who they want to save over cigarettes, was not only a form of solidarity but also a call to action.

The beauty of the convention was that it pulled away the nihilistic curtain that often obstructs the view of people like myself. Oftentimes, it feels like death and destruction will be all I write about until the drug war takes my life as well.

And there is some truth to that: The world is often a very dark place. But it doesn't have to be.

We must all acknowledge that the stakes are high. The harm reduction movement faces an uphill battle. But just by showing up last week, advocates demonstrated that there is strength in numbers — and we are not to be fucked with.

Read my latest piece: "Baltimore media outlets may be exacerbating an already unprecedented overdose crisis"

When a mass overdose event hospitalized nearly 30 people in Baltimore’s Penn North neighborhood in July, reporters descended upon the low-income Black community. Some photographed victims on gurneys while harm reduction workers and paramedics scrambled to save lives.

The resulting local coverage contained a barrage of misinformation and fearmongering at the expense of vulnerable Baltimoreans, echoing journalists’ longstanding failure to responsibly cover those who use drugs. False reports brimming with stigmatizing language flooded the internet and TV waves, illustrating what public health workers and researchers have long known: words matter.

Read the full newsletter here.

Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data has been updated with the latest local, state and national data

There were 778 overdose deaths in Baltimore in 2024, a 25.4% decrease from the year prior, according to preliminary data.

In the 12-month period ending in September, Baltimore saw 536 deaths, a death rate of 91.5 per 100,000 people. Statewide, there were 1,296 deaths, a death rate of 21 per 100,000 people.

The data indicates that fatal overdoses continue to trend downward after years of climbing, though poor Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore continue to suffer the most.

Check out Mobtown Redux's Overdose Data Dashboard here.

Click here to learn more about harm reduction resources in the Baltimore area.

Filter: "Remembering Peter Krykant, Who Knew Harm Reduction Couldn’t Wait

It’s been a few months since Peter Krykant’s passing in June, at the age of 48. He hit the global harm reduction scene with a bang. The story of him running an unauthorized overdose prevention site from a van in Glasgow, after years of inaction from the Scottish and British governments, catapulted him into the spotlight.

Krykant’s knack for public speaking and passion for helping people transform their lives were already clear from his past work and advocacy in Alcoholic Anonymous. But his campaigning became more urgent as he continued to see too many people hurting and dying around him. With British drug policy infamously resistant to change, he took action. He knew that something needed to change to keep people alive. Not in a few years, not after lengthy data collection processes, not after a shift in political priorities—now.

Click here to read the full article.

Comments